After the annual Advent of Code event, it's time for my annual review of my solutions and how it went. (I've also written reviews of the 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023 Advents of Code.)

The first thing to say is a huge thank you to Eric Wastl and the team for creating the puzzles, organising the event, and providing superb support throughout. I know what's involved putting together these kinds of events, and just how much work it is to nail down all the possible loose edges. More thanks to the Reddit community for being universally helpful and supportive.

For some commentary on the Advent of Code participants, take a look at the Unofficial AoC survey results.

I enjoyed reading some writeups by other people of their solutions to Advent of Code. In no particular order, the ones I look at are:

The puzzles

The quality of the puzzles in Advent of Code continues to be a high point of the event. The tasks are nicely graduated over the month, and even the hardest puzzles typically taking only a few hours to solve. They're all accessible, and the first few puzzles seem very accessible to even beginner programmers.

There were a few comments online that some puzzles had long descriptions that needed careful reading. I didn't particularly find that; some descriptions were long, but they were carefully setting out the detail of the specification. It's clear the puzzles had gone through extensive testing to get the descriptions accurate and comprehensive, so everyone knew what they had to do.

In particular, the examples given in each puzzle description clearly covered just about all the possible ambiguities, and there were no "trick" questions where the actual input was substantially different from the examples.

There seemed to be fewer puzzles this year that built on previous ones. There were a lot of grid-based puzzles, and path-finding turned up in several of them, but that was about it. Many of the puzzles had a part 2 that I couldn't predict from part 1, and that caused me some additional pain in reworking my solution to cover both parts.

Programming concepts and language features

Advent of Code seems to continue the trend towards needing fewer "advanced" programming concepts and algorithms. The only new-to-me algorithm was the Bron-Kerbosch algorithm for finding maximal cliques in a graph on day 23. There were no overly-complex uses of discrete maths or number theory (such as the Chinese remainder theorem, a perennial favourite), no complex data structures to define, and not much used from the realms of theoretical computer science.

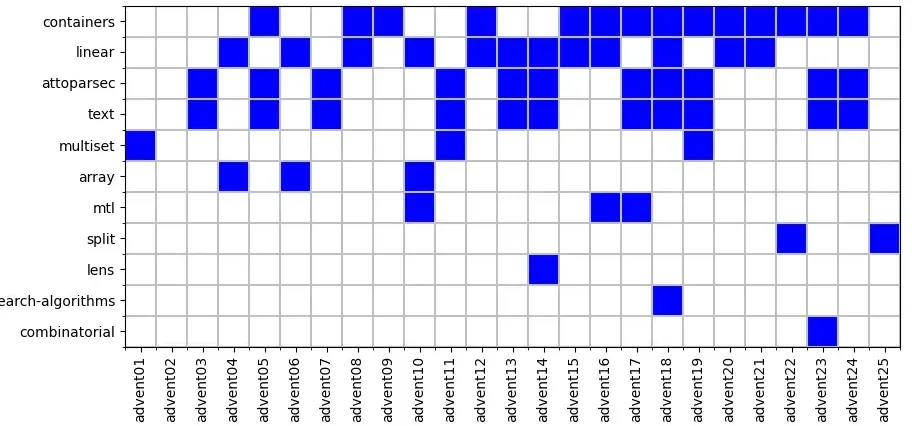

This is reflected in the range of packages and modules I used. (In the Haskell ecosystem, a module is a particular library, typically providing a single data type or algorithm and a package is a bundle of modules that go together.) The table below shows what packages I used and how often. containers provides workhorse data structures like Map and Set. I use linear for coordinates (and there were a lot of grid-based problems). attoparsec and text are used together for parsing of input, typically the inputs that aren't grid based. As you can see, beyond those, the number of package uses drops of very rapidly. Unlike previous years, I only used lens once.

| Package | Number of uses |

|---|---|

| containers | 14 |

| linear | 12 |

| attoparsec | 11 |

| text | 11 |

| array | 3 |

| mtl | 3 |

| multiset | 3 |

| split | 2 |

| combinatorial | 1 |

| lens | 1 |

| search-algorithms | 1 |

Looking at the package use per day shows how some packages get used together.

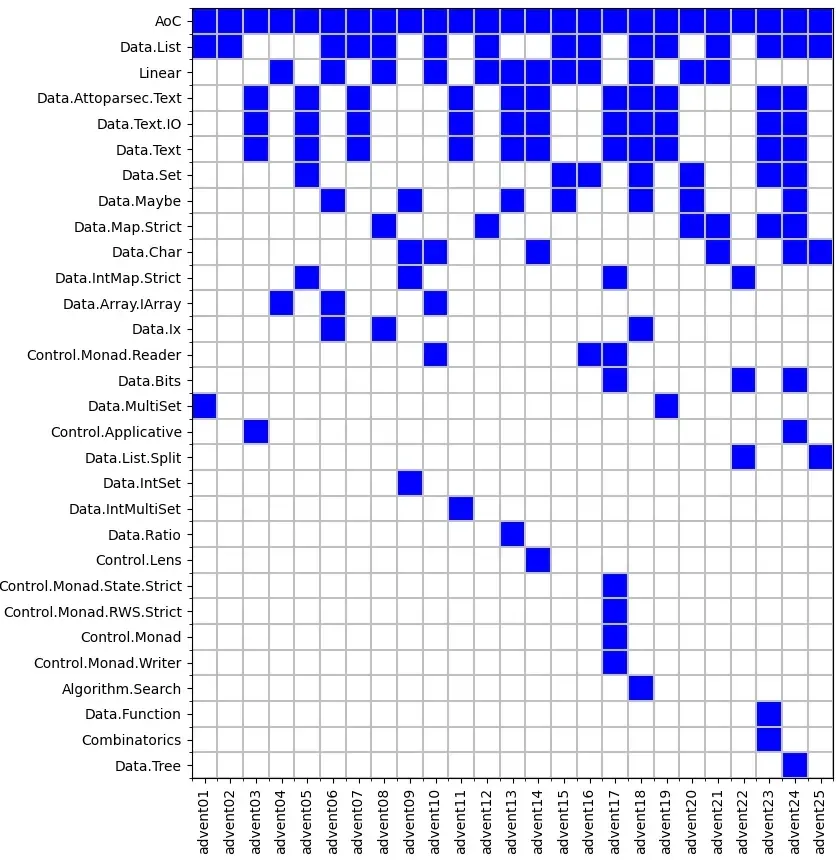

Looking at the modules used gives a bit more detail. The AoC module is my own that consists of little more than a convenience function for loading data files. This shows that Data.List does a lot of work in many problems, and various flavours of Map and Set get used a lot. Data.Maybe and Data.Char turn up a few times for general utility. Data.Bits turns up a couple of times for bitwise operations.

| Module | Number of uses |

|---|---|

| AoC | 25 |

| Data.List | 15 |

| Linear | 12 |

| Data.Attoparsec.Text | 11 |

| Data.Text.IO | 11 |

| Data.Text | 11 |

| Data.Set | 7 |

| Data.Maybe | 7 |

| Data.Map.Strict | 6 |

| Data.Char | 6 |

| Data.IntMap.Strict | 4 |

| Data.Array.IArray | 3 |

| Data.Ix | 3 |

| Data.Bits | 3 |

| Control.Monad.Reader | 3 |

| Control.Applicative | 2 |

| Data.MultiSet | 2 |

| Data.List.Split | 2 |

| Data.IntSet | 1 |

| Data.IntMultiSet | 1 |

| Control.Monad.State.Strict | 1 |

| Control.Monad.RWS.Strict | 1 |

| Control.Monad | 1 |

| Data.Function | 1 |

| Data.Ratio | 1 |

| Control.Lens | 1 |

| Control.Monad.Writer | 1 |

| Combinatorics | 1 |

| Data.Tree | 1 |

| Algorithm.Search | 1 |

Looking at the diagram of when each package is used shows there's not much correlation between what modules are used where.

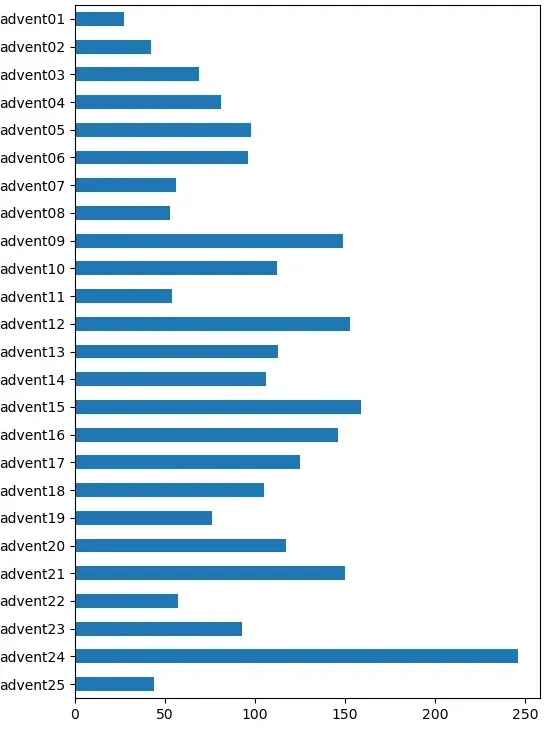

Finally for this section, a quick-and-dirty look at program size. Haskell is often much terser than imperative languages and this is reflected in the sizes of the programs. Note that I don't have a bespoke library of utilities to draw on, like some competitive programmers. Apart from finding the name of the input file, all the code to solve each puzzle is in the source code for that day. Lines of code are found with a basic wc -l, so include blank lines, comments and similar.

| Day | Lines of code |

|---|---|

| advent01 | 27 |

| advent02 | 42 |

| advent03 | 69 |

| advent04 | 81 |

| advent05 | 98 |

| advent06 | 96 |

| advent07 | 56 |

| advent08 | 53 |

| advent09 | 149 |

| advent10 | 112 |

| advent11 | 54 |

| advent12 | 153 |

| advent13 | 113 |

| advent14 | 106 |

| advent15 | 159 |

| advent16 | 146 |

| advent17 | 125 |

| advent18 | 105 |

| advent19 | 76 |

| advent20 | 117 |

| advent21 | 150 |

| advent22 | 57 |

| advent23 | 93 |

| advent24 | 246 |

| advent25 | 44 |

The median size is 98 lines, the mean is 101. The day 24 solution is a lot longer than the others.

It may be easier to see this graphically.

Performance

The performance promise is that

[E]very problem has a solution that completes in at most 15 seconds on ten-year-old hardware.

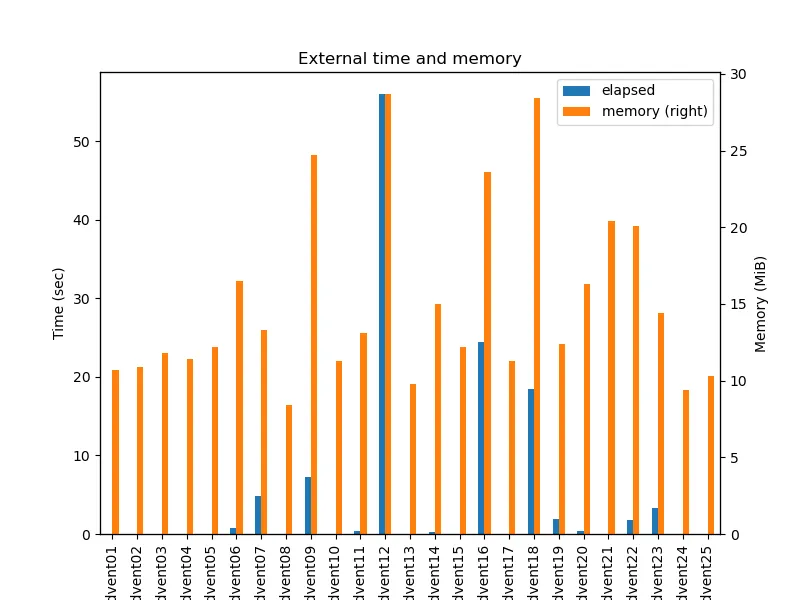

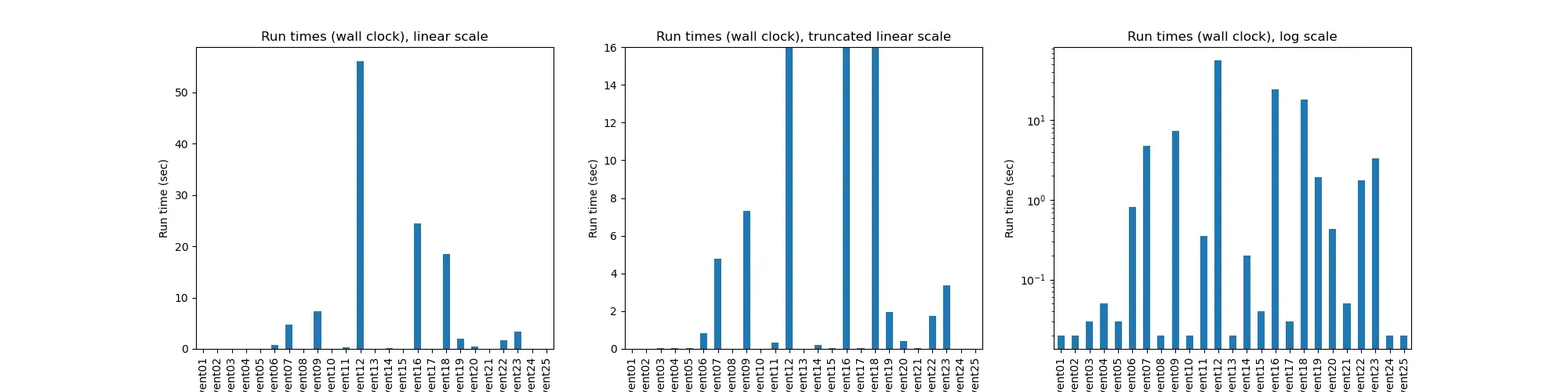

That was true for most solutions, but not all. Most took a second or less, a couple took a few seconds, and three took well over the 15 second limit.

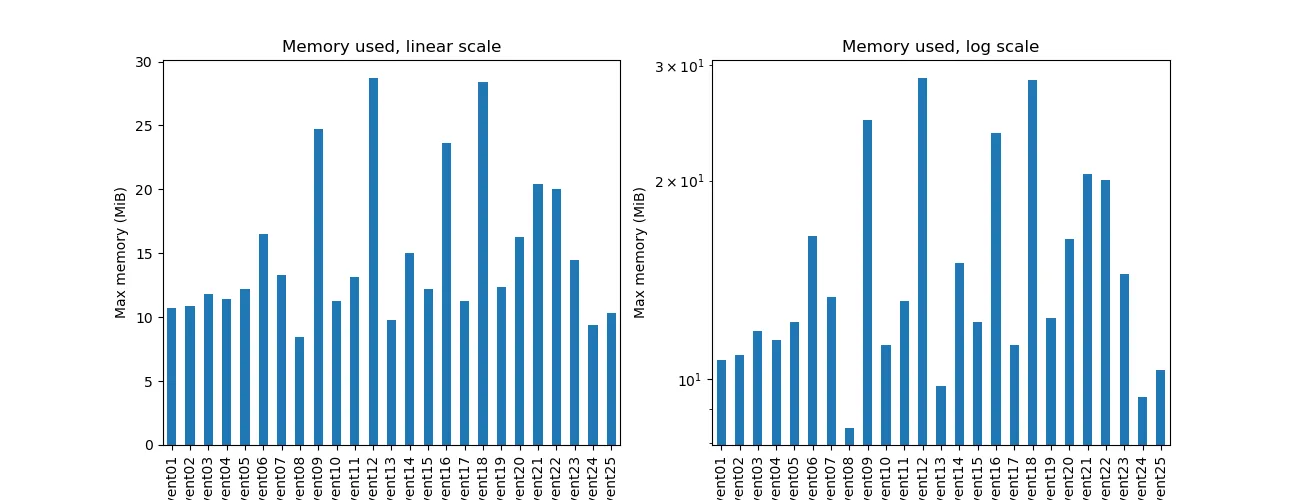

Memory use was pretty frugal thoughout, with only a few tens of MiB used each day.

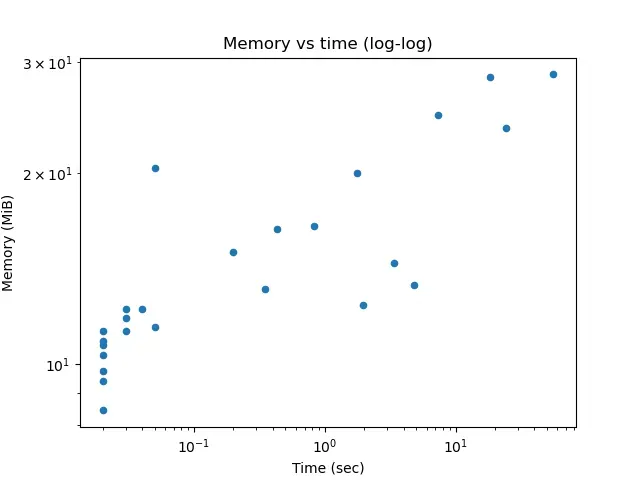

Memory use and time taken seem to correlate, as seen on this scatter diagram (note that both axes have log scales).

The details of time and memory used are in the table.

| Program | Time (sec) | Max memory (MiB) |

|---|---|---|

| advent01 | 0.02 | 10.69 |

| advent02 | 0.02 | 10.88 |

| advent03 | 0.03 | 11.81 |

| advent04 | 0.05 | 11.44 |

| advent05 | 0.03 | 12.19 |

| advent06 | 0.82 | 16.50 |

| advent07 | 4.78 | 13.31 |

| advent08 | 0.02 | 8.44 |

| advent09 | 7.30 | 24.74 |

| advent10 | 0.02 | 11.25 |

| advent11 | 0.35 | 13.12 |

| advent12 | 55.98 | 28.69 |

| advent13 | 0.02 | 9.75 |

| advent14 | 0.20 | 15.00 |

| advent15 | 0.04 | 12.19 |

| advent16 | 24.46 | 23.62 |

| advent17 | 0.03 | 11.25 |

| advent18 | 18.42 | 28.42 |

| advent19 | 1.95 | 12.38 |

| advent20 | 0.43 | 16.31 |

| advent21 | 0.05 | 20.44 |

| advent22 | 1.75 | 20.06 |

| advent23 | 3.36 | 14.44 |

| advent24 | 0.02 | 9.38 |

| advent25 | 0.02 | 10.31 |

Generally, these solutions aren't well optimised, except where a good algorithm or representation was needed to get a solution in less than a few hours or days. Expect to see some posts in the future where I optimise the three very slow solutions.

Code

You can get the code from my locally-hosted Git repo, or from Codeberg.