After the annual Advent of Code event, it's time for my annual review of my solutions and how it went. (I've also written reviews of the 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 , and 2024 Advents of Code.)

As always, huge thanks to Eric Wastl and team for putting together the event. This year, Eric took the entirely sensible decision to reduce the number of puzzles from 25 to 12. I know why! I've done a couple of these sorts of challenge sets for some of my students, so I know just how long it takes to come up with the idea for a puzzle, rigorously test that it works, write up a clear and unambiguous description, and all the other bits that go into putting together such an event.

The Reddit community continues to be a great place of welcome and support, but I didn't pop in there as much this year. There's also the Advent of Code hashtag on Mastodon. As for who's doing the event, the Unofficial AoC survey continues to inform.

I enjoyed reading some writeups by other people of their solutions to Advent of Code. The main three I keep an eye on are:

- Justin Le for better Haskell than I can produce

- Juha-Matti Santala for excellent descriptions of solutions, and links to other solution blogs

- Peter Norvig for excellent insight into solutions

In no particular order, other ones I look at are:

The puzzles

As always, the puzzles are excellent. The shorter event this year meant there was inevitably a narrower range of puzzles than previous years. All the puzzles were accessible and none required specialist knowledge or detailed techniques. There were a couple that benefited greatly from a quick look on Wikipedia and elsewhere for some algorithms for specific problems.

There was only one "trick" question, which was day 12. The examples suggested that you needed to do something far more complicated than what was needed for the correct answer. Similarly, day 10 part 2 pretty much required the use of an external library to solve, rather than building your own linear equation solver.

Programming concepts and language features

As with previous years, only a basic programming knowledge was needed for most puzzles. Some form of caching/memoisation/dynamic programming was useful for a couple of puzzles. Knowing how to find and use an external library for linear equations was needed for day 10. Apart from that, I only used some simple features of Haskell. No typeclasses, monoids only turned up once, monads only turned up once.

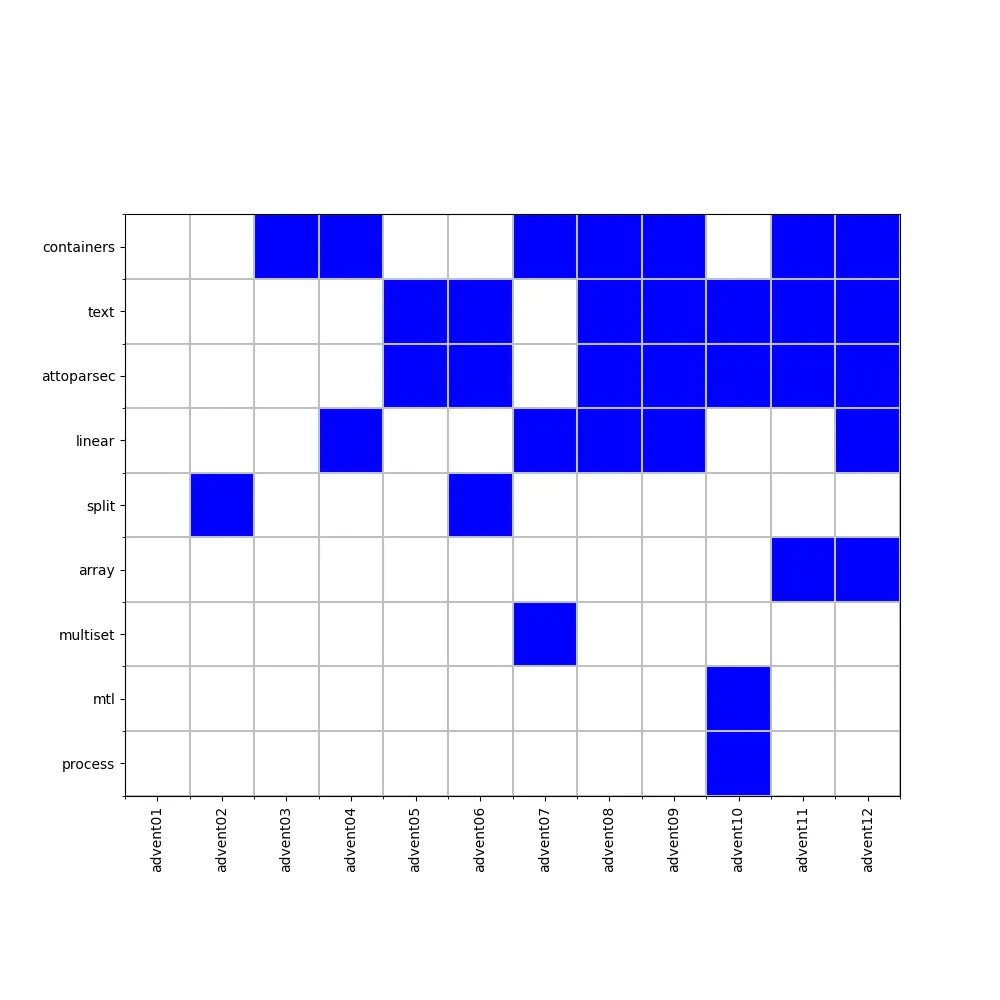

This is reflected in the range of packages and modules I used. (In the Haskell ecosystem, a module is a particular library, typically providing a single data type or algorithm and a package is a bundle of modules that go together.) The table below shows what packages I used and how often. containers provides workhorse data structures like Map and Set. I use linear for coordinates (and there were a lot of grid-based problems). attoparsec and text are used together for parsing of input, typically the inputs that aren't grid based. As you can see, beyond those, the number of package uses drops of very rapidly.

| Package | Number of uses |

|---|---|

| attoparsec | 7 |

| text | 7 |

| containers | 7 |

| linear | 5 |

| array | 2 |

| split | 2 |

| mtl | 1 |

| process | 1 |

| multiset | 1 |

Looking at the package use per day shows how some packages get used together. There's not a lot of correlation.

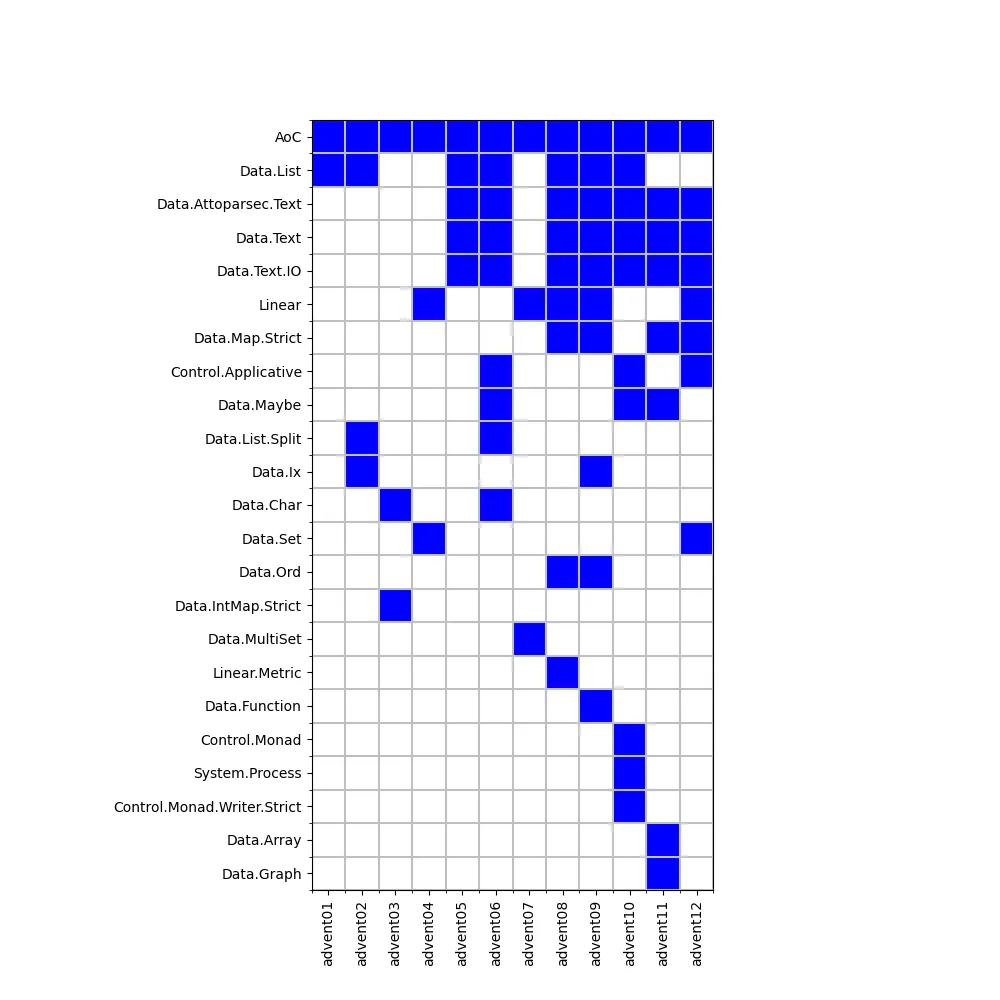

Looking at the modules used gives a bit more detail. The AoC module is my own that consists of little more than a convenience function for loading data files. This shows that Data.List does a lot of work in many problems. I use Linear for coordinates. Other modules turn up for general utility.

| Module | Number of uses |

|---|---|

| AoC | 12 |

| Data.Attoparsec.Text | 7 |

| Data.List | 7 |

| Data.Text | 7 |

| Data.Text.IO | 7 |

| Linear | 5 |

| Data.Map.Strict | 4 |

| Control.Applicative | 3 |

| Data.Maybe | 3 |

| Data.List.Split | 2 |

| Data.Char | 2 |

| Data.Set | 2 |

| Data.Ord | 2 |

| Data.Ix | 2 |

| Control.Monad | 1 |

| Control.Monad.Writer.Strict | 1 |

| Data.Array | 1 |

| Data.IntMap.Strict | 1 |

| Data.Function | 1 |

| Data.Graph | 1 |

| Data.MultiSet | 1 |

| Linear.Metric | 1 |

| System.Process | 1 |

Looking at the diagram of when each package is used shows there's not much correlation between what modules are used where.

Finally for this section, a quick-and-dirty look at program size. Haskell is often much terser than imperative languages and this is reflected in the sizes of the programs. Note that I don't have a bespoke library of utilities to draw on, like some competitive programmers. Apart from finding the name of the input file, all the code to solve each puzzle is in the source code for that day. Lines of code are found with a basic wc -l, so include blank lines, comments and similar.

| Program | Lines in program file |

|---|---|

| advent01 | 43 |

| advent02 | 117 |

| advent03 | 44 |

| advent04 | 58 |

| advent05 | 74 |

| advent06 | 70 |

| advent07 | 83 |

| advent08 | 103 |

| advent09 | 160 |

| advent10 | 179 |

| advent11 | 84 |

| advent12 | 78 |

The median is about 80, the mean is 91 lines.

Performance

The performance promise is that

[E]very problem has a solution that completes in at most 15 seconds on ten-year-old hardware.

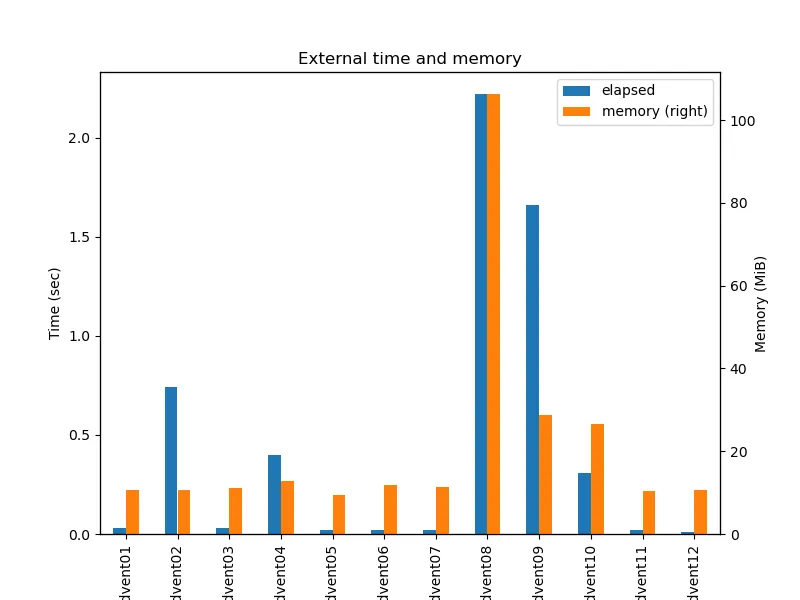

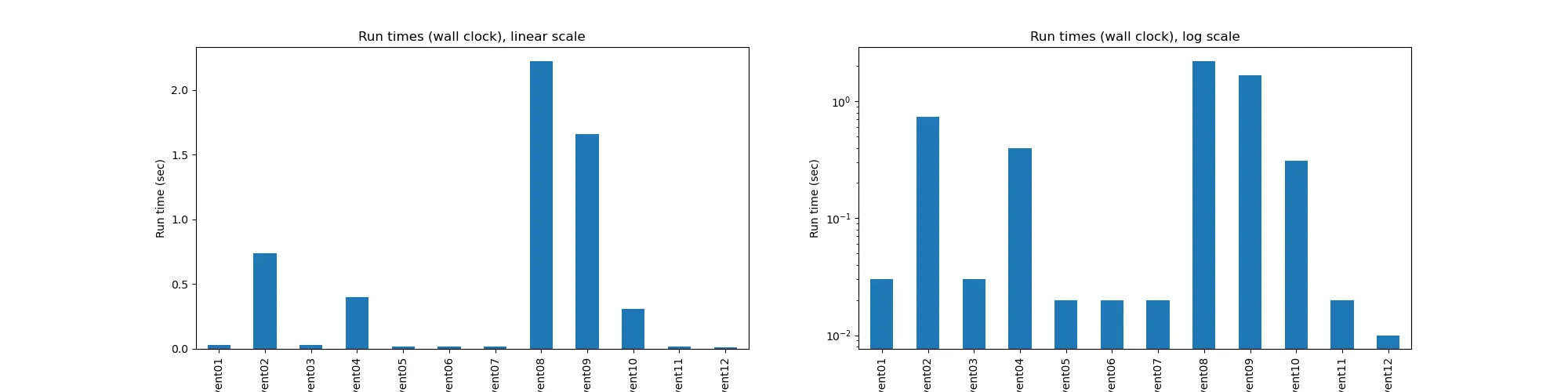

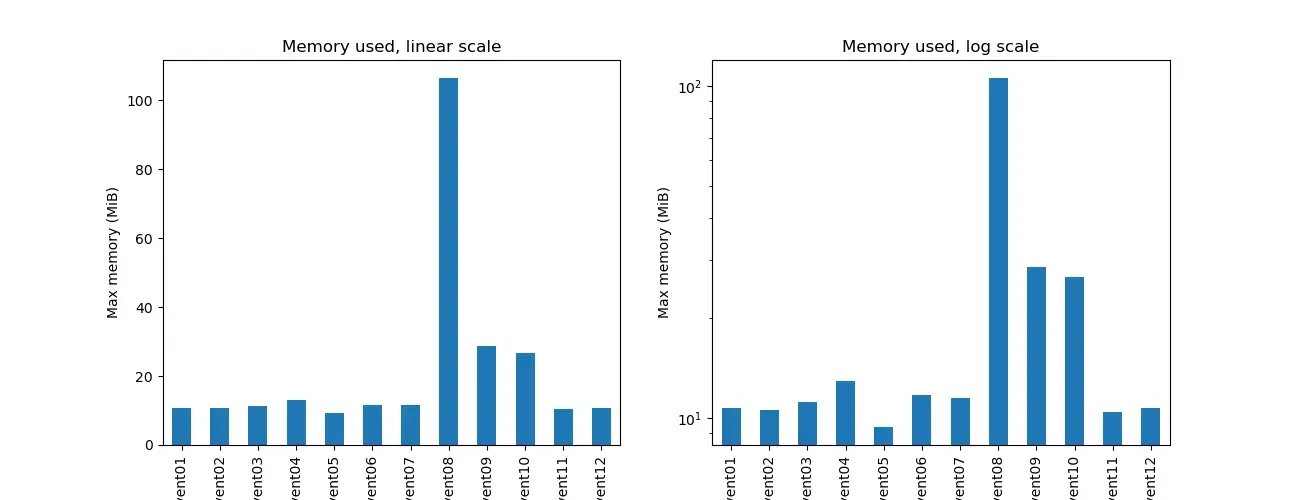

That was true for all my solutions, once I optimised the day 9 solution. Most took a second or less, a couple took a couple of seconds. Similarly, most programs used about 10Mb of memory, with only day 8 using more.

| Program | Time (seconds) | Memory (Mb) |

|---|---|---|

| advent01 | 0.03 | 10.71 |

| advent02 | 0.74 | 10.59 |

| advent03 | 0.03 | 11.17 |

| advent04 | 0.40 | 12.91 |

| advent05 | 0.02 | 9.38 |

| advent06 | 0.02 | 11.72 |

| advent07 | 0.02 | 11.47 |

| advent08 | 2.22 | 106.30 |

| advent09 | 1.66 | 28.64 |

| advent10 | 0.31 | 26.63 |

| advent11 | 0.02 | 10.48 |

| advent12 | 0.01 | 10.71 |

Here are charts for the time and memory use.

Generally, these solutions aren't optimised at all, beyond choosing and appropriate representation and algorithm. The only optimisation was in day 9, where I used "compressed coordinates" to reduce the time and space needed.

Code

You can get the code from Codeberg.